John Montgomery: Good afternoon Thomas, and thanks so much for chatting with me. Moving into what we’re talking about today, I’d love to hear your thoughts on the role of having a well-defined brand in driving innovation. The word “innovation” is so widely used, it means different things to different people. How important do you think a strong brand or story is when you’re trying to foster innovation within your company?

Thomas Chalberg: That’s an interesting question. Innovation is about mindset—it’s saying, “We’re going to do things differently.” The opposite of innovation is just repeating what’s already been done, like copy-pasting from big pharma. In Silicon Valley, it’s understood that big companies don’t innovate. It’s not a criticism, but rather a structural issue—they acquire innovation rather than create it. Large companies play a crucial role in delivering medicines to patients, but smaller companies are more nimble, and able to adapt and try things quickly, which allows for innovation.

Small companies innovate because they’re nimble. We can adapt quickly, move faster, and try and fail more easily than big companies. The incentive and governance structures in large companies often don’t allow for the processes that lead to innovation. Of course, great things have come from big companies, especially when they work together with smaller companies or academics. But as a rule, smaller companies have a structural advantage in innovation. Sorry, did that answer your question?

JM: You’re already answering part of it, which is great. I was asking about the role of a strong brand or story in fostering innovation. You’ve touched on that, and I’d love to hear more about how you’ve leveraged design or intentional branding to drive outcomes, whether that’s innovation or something else.

TC: That’s an interesting point. Design, art, and branding speak to us on a subconscious level. When you visit a website and it looks outdated—like something from 1997 with basic fonts and black-and-white photos—you get an impression about the company, whether it’s accurate or not. A modern, artful design gives a sense that the company is forward-thinking and innovative. In tech, you see this all the time. A well-designed website can make you feel like you’re living in the future, whereas I’ve seen certain “big pharma” websites that make you feel like you’re stuck in the past.

In biotech, we live somewhere between these two worlds. If your website looks too “techy,” people might wonder if you’re serious scientists because this is a more mature industry where credibility and experience matter. It’s a regulated, traditional field, but if you can edge away from that outdated, big pharma feel toward something more modern, it communicates forward thinking and innovation. It shows prospective employees, investors, and the media that you’re a company doing things differently, not stuck in the past.

For example, when you go to the Genascence website, there’s a new image every time you refresh, and it’s simple but constantly changing. It gives the impression of a company that’s dynamic, forward-thinking, and embracing technology, rather than one bogged down by corporate bureaucracy.

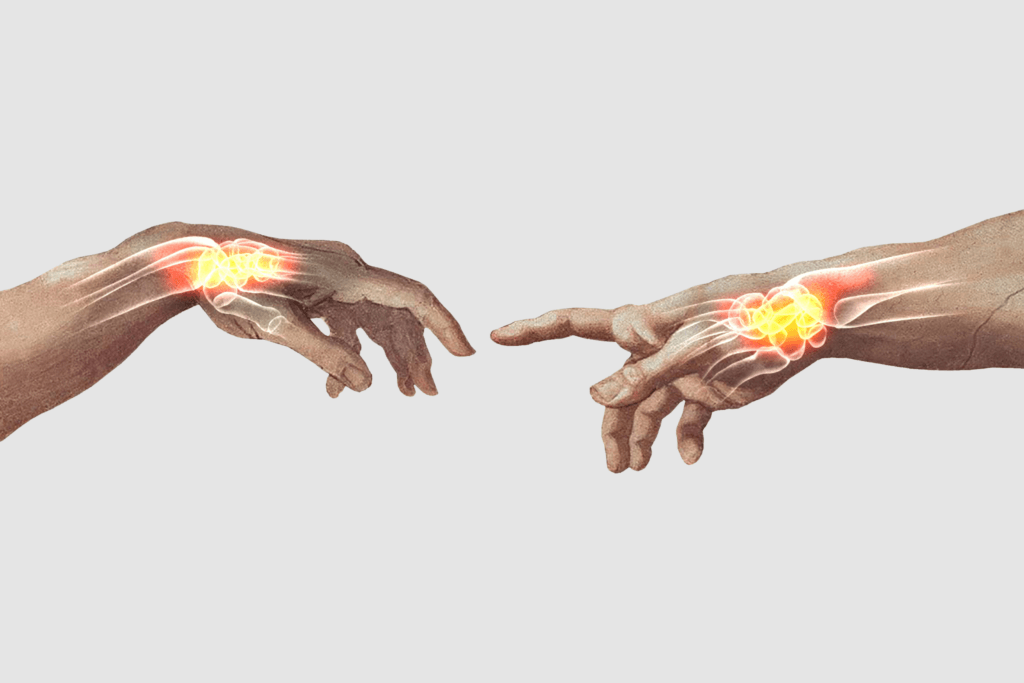

JM: That’s interesting. I remember when we first started talking, you mentioned that the space you’re in—osteoarthritis and musculoskeletal issues—wasn’t seen as a particularly “sexy” area of biotech. It was considered a more stagnant field. You felt like you had to work harder to get investors to see that you were doing something different. Have you noticed a change in perception since we did the branding work together?

TC: Honestly, it’s hard to measure. It’s not like people say, “I visited your website and now I see you’re doing things differently.” But almost everyone we talk to—whether it’s a potential employee, an investor, or anyone else—has visited the website. That’s just the world we live in. People will Google you, look at your LinkedIn, visit your site, and check out some basic facts. The feedback we consistently hear is that people are excited about what we’re doing and see it as innovative. Can we tie that directly to specific design elements? Not really. But we’ve quickly gained recognition in the musculoskeletal and osteoarthritis space, and part of that is because we’ve differentiated ourselves. We have a brand that communicates innovation, and we hear that repeatedly: “I love what you’re doing.”